Why “sleep”?

In a previous article, we talked a bit about narcolepsy as one of the very intriguing sleep disorders. It was perhaps easy to understand why people suffering from narcolepsy could have a pretty hard time performing several normal tasks; however, most of us would probably relate less to narcolepsy. But something which almost everyone can agree to have experienced regularly, in one way or another, is sleep. In comparison with disorders associated with it or derived from its impairments, sleep itself might not seem so interesting. We all do it and we can’t deny how much we enjoy it and long for it after it stops. Yet, there is much more to sleep than we think.

Sleep is very important for the normal functioning of any being. For animals as well as for humans, sleep helps in energy conservation, body restoration, predator avoidance and learning aid. Different animals have different sleep-wake cycles, from nocturnal animals (like rodents), which sleep during the day and are active at night, and animals which sleep with only half of the brain (like dolphins), all the way to diurnal animals, like humans. Although humans are advised to sleep approximately 8 hours per night, some people sleep very little (around 2-3 hours/night) and still function perfectly fine. An example of such a situation is presented in the textbook of Rosenzweig et al. (pg. 389).

But what triggers sleep and how is it regulated?

Most of us are certainly able to recall a dream the next morning and the memory of that dream is usually accompanied by feelings and emotions we sometimes do not even experience in real life. We are often under the impression that our dream has lasted the whole night. In fact, there are two stages of sleep, one of which is associated with the formation of dreams. These stages, known as non-REM sleep and REM sleep, succeed each other in cycles lasting approximately 90 minutes. Just to define the terms, REM means rapid eye movement and represents the part of sleep with the most increased brain activity. Interestingly, during REM the brain seems to consume more oxygen than during arousal!

Normally, when we fall asleep we slip into the non-REM stage or the slow-wave sleep (SWL). This, in turn, is divided into four other stages: from light sleep to very deep sleep. During this phase, the brain is said to be truly resting and the body appears to repair its tissues. No dreams can be seen! The movement of the body is reduced, but not because the muscles are incapable of moving; it’s the brain which does not send signals to the body to move! One interesting feature of non-REM sleep is sleep-walking. This peculiar behaviour some people show while asleep usually takes place during the fourth (last) part of the non-REM sleep, when the person is the deepest sleep. This is the reason why it is very difficult to wake a sleepwalker up.

In turn, REM sleep (which starts after a 30-minute non-REM period) is the “active” part of our sleep. This time, the brain sends commands to the body, but the body seems to be in an almost complete state of atonia (immobility). The heart rate and breathing become irregular and the brain is not resting. In fact, our dreams happen during this time and more importantly, our long-lasting memories are thought to be integrated and consolidated.

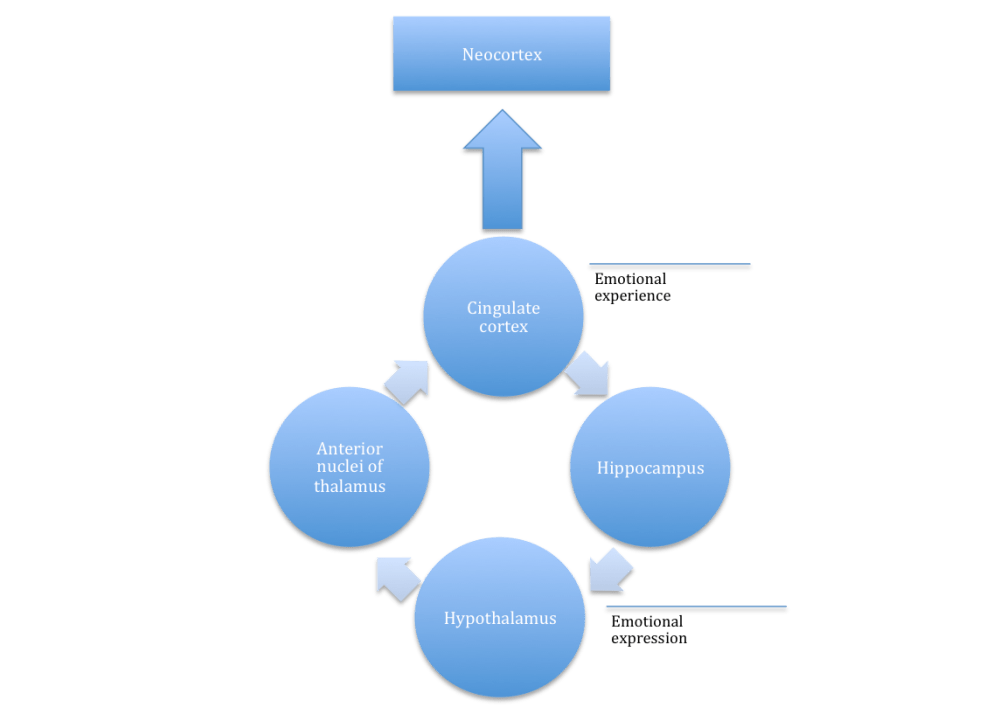

When it comes to sleep regulation, many neuroendocrine systems and brain functions play a role. The circadian (or sleep-wake cycle), which is controlled primarily by the suprachiasmatic nuclei, in the hypothalamus, need special attention. For the purpose of this article, I won’t focus on the circadian clock now, but I will come back to this in a future article. The autonomic nervous system and parts of the brain such as the brainstem, the limbic system, especially the amygdala, and the forebrain modulate different aspects and stages of sleep. Amygdala, which I mentioned in a previous article about emotions and decision-making, is a brain region involved in the emotions such as fear. It also appears to be very active during REM-sleep and may account for the awful nightmares we often experience.

Many cognitive functions, such as intelligence, performance and emotions are associated with disrupted non-REM as well as REM sleep. To be more specific, REM-sleep loss appears to be associated with increased anxiety and stress and loss of emotional neutrality – this means that a person deprived of REM-sleep is more likely to react negatively to neutral emotional stimuli than in normal conditions. The explanations vary, but most of the studies agree that impaired REM sleep triggers increased release of noradrenaline, hyperactivity of amygdala and decreased function of prefrontal cortex (which tells “stop!” to the amygdala when it goes crazy). At the same time, people deprived of non-REM sleep could experience depression, due to deficiency in another neurotransmitter, this time an inhibitory one, called GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid). Other problems linked to sleep deprivation are attention deficits, working memory impairments and usually affected divergent thinking (creative, innovative thinking).

Aging people seem to sleep less and this deprivation is also associated with conditions like Alzheimer’s. Moreover, sleep deprivation can kill you! Sustained sleep loss can cause low immune system and drop in body’s temperature, which can make bacterial infections fatal. Another consequence of sleep loss is increased metabolic rate, which leads to weight loss and eventually death. Don’t think this could be a good idea for a diet! More like for “die”!!! Having said that, most people should try their best to get enough hours of sleep.

I hope this article convinced you of the importance of sleep and as usual, any questions or comments are welcome 🙂

Further information:

Article 1 – about REM-sleep and emotional discrimination

Article 2 – about non-REM sleep and GABA

Article 3 – about how sleep loss affects behaviour and emotions

Article 4 – a review on many articles about the link between sleep deprivation and emotional reactivity and perception

Bear et al., 2006. Neuroscience – Exploring the Brain. s.l.:Lippincott Williams & Wilknins

Rosenzweig et al., 2010. Biological Psychology – An Introduction to Behavioural, Cognitive and Clinical Neuroscience. 6th edition. Sinauer Associates Inc.,U.S., pg. 380-401

Both images by Gabriel Velichkova